Desert Prince Sample Chapter: Darin

349 AR

My name is Darin Bales, and everyone says my da saved the world.

It’s fine, I guess. He died before I was born so I don’t really miss him, and I’ve no shortage of family – blood and otherwise.

Saving the world is the kind of reputation that can stick to a family. Folk I’ve never met give me gifts and let me get away with just about anything. But sometimes I catch them staring, like they’re expecting me to do something amazing.

And when I don’t, I can smell their disappointment.

Mam tried to keep me from the worst of it. Brought me back to Tibbet’s Brook, the village on the edge of nowhere where she and Da grew up. Most of the folk here have ale stories about Da too, but they didn’t know him in the war. Instead they embellish childhood antics into legends worthy of a Jongleur’s tale, taking pride in having known the Deliverer when he was knee-high.

Sometimes it feels like everyone knew my da except me.

* * * * *

I feel dawn coming without even looking at the window. It is still full dark by most folk’s reckoning, but my night eyes can see the coming light wash colour through the sky.

I don’t like sunrise. The light stings as it takes away my night eyes, leaving me half-blind until sunset. I feel the sun’s heat on my skin like the touch of a hot skillet. I burn easily if I forget to cover up.

Most of the world wakes with the sun. Plants tilt and insects buzz to life as their flowers open. Animals rouse and people wake. I hear every footstep, the sound of countless creatures stretching and rising and clomping about in search of breakfast. I smell every food, every bodily function, every lather of soap.

All of it, all at once. So much that it can be overwhelming if I don’t take care.

I want to flee, but first, like every morning, there’s chores.

I step over the threshold of Grandda Jeph’s farmhouse before the cock crows. The yard is safe, but Grandda doesn’t like me doing chores too early. Says it upsets the animals.

I snatch the cloth-lined wicker basket from its spot by the door and run to the chicken coop, ignoring the squawks of protest as I snatch eggs and am gone before the birds even realize I’m there, juggling them into the basket.

Grandda doesn’t like me juggling the eggs, but I need the practice if I’m to become a Jongleur. I’ve given this a lot of thought. Other jobs just seem like too much work, and no one looks twice when a strange Jongleur comes to town. I could go somewhere no one knows me, and they just treat me like regular folk. And if they figure it out, I go somewhere else.

I open the henhouse door and leave a scattering of seed in the yard, then dash indoors to leave the eggs on the kitchen counter while the house still sleeps. An instant later I’m on a stool beneath the first of the cows. They’re no less surprised than the hens as I blur through their stalls, but happy for a quick, efficient milking.

The windows of the farmhouse are still dark as I leave the milk in the coldhouse and rush to the rest of my chores. Feedbags for the horses and slop for the pigs. The wellhouse, the curing shed, the smokehouse, the silo. Like a wind blowing through the farm, I pay each a hurried visit, racing against the dawn.

The old rooster stirs. I hate that bird. It inhales just as I finish filling the firebox – the last of my chores. I cover my ears and flee, getting as much distance as I can before it begins to shriek.

* * * * *

I cut overland through fallow fields and thick stands of trees, keeping to the shade as much as I can. I skip over a wide stream, seeing faint indentations worn into the stones by generations before me. Reckon my da was one of them. This is the most direct route from the farm to Town Square. Stepping where he used to step, like reading his old journals, lets me know a little bit of him.

The sun is only a sliver on the horizon when I reach Town Square, but the smell of Aunt Selia’s butter cookies is already in the air. She’s left a tray of them by her window to cool. My mouth waters and my stomach grumbles to life.

Selia Barren is Town Speaker and head of the militia in Tibbet’s Brook. She ent really my aunt, but Mam always says family’s about more than blood. The other kids call her Old Lady Barren. Everyone’s scared of her, except me.

I scamper up her wall and peek in the window. The kitchen is empty. Quickly I stuff a cookie into my mouth, letting it overwhelm my senses. In an hour they will stiffen into the hard, crumbly biscuits Aunt Selia likes with her tea, but fresh from the oven, they are still warm, fragrant, and soft. The recipe is simple, letting the butter rule without confusing it with too many other flavours. I use both hands to stuff more into my pockets.

‘Darin Bales, I knew it was you, stealing my cookies!’

I freeze as Selia storms into the kitchen. I should have scented her as she lay in wait, but I was too focused on the smell of the cookies.

‘Sorry, Aunt Selia,’ I try to say, but my teeth are full of cookie, and it comes out ‘thorry and thelia’.

Her expression doesn’t change, but her scent changes from irritation to amusement, and I can see the muscles around her mouth twitch. ‘You could just ask, Darin. I’ve never denied you a cookie.’

It’s true, but Selia always offers the oldest cookies, yesterday’s batch that sits in the crock on her table.

I swallow. ‘Better when they’re fresh.’

Selia crosses her arms. ‘You could still come in and ask.’

I glance over my shoulder at the rising sun. ‘Ent got time.’ I snatch another cookie and set off running before she can shout.

The schoolbell rings, but I put my hood up, keeping to the shade as much as I can on the run to Soggy Marsh. Still, the light stings my eyes and makes me dizzy.

The Marsh gets an unfair reputation. When folk think of it, they think of the rice paddies – wet, bug-infested, and smelly. But the outskirts of the wetlands are actually quite nice, with lots of fishing holes and cool shady spots far from folk. Perfect for sleeping away the heat of morning.

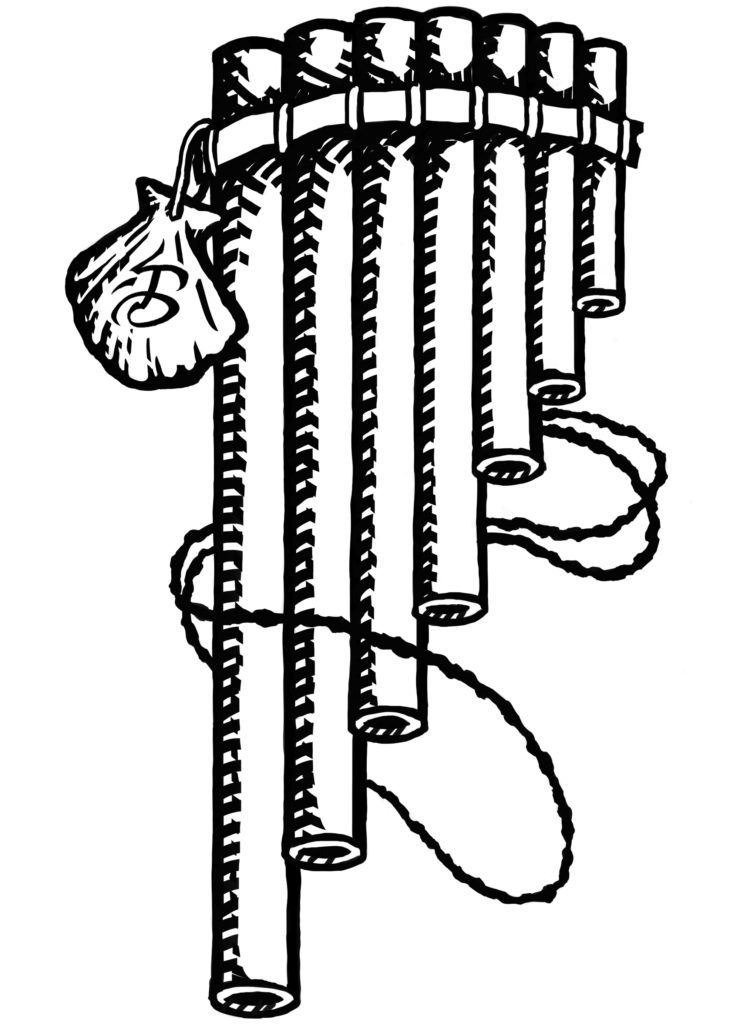

I wake past midday, feeling refreshed. I finish the cookies in my pocket as I go down to the swimming hole to cool off. After a quick swim I climb a tree and take out my pipes, testing the reeds. One of the notes is sour. I close my eyes and run my thumb over the reed. There’s a hairline crack.

At the water’s edge I cut a new reed, then return to my perch and take out my tuning kit. I shape the reed and treat it with quick-drying resin, then carefully unweave the rough cord that binds the pipes tightly together. By the time I clean them all, the resin is dry and I replace the sour reed. Lashing them back together to act as a single unit is tricky, but I’ve done it so many times now it’s become second nature.

Again I test the notes. Satisfied this time, I begin to play.

I hear voices, soon after. Marsh kids released from the schoolhouse for the day, come down to swim.

There’s laughter as they hear my music. They spin around, staring up at the trees, trying to guess where the music is coming from.

‘Schoolmam’s given up on you comin’ back, Darin Bales!’ Ami Rice calls. ‘She don’t even call you on the roll anymore!’

I make my tune a little more playful, laughing through the music. Nothing could drag me back to the chaos of that crowded classroom.

‘Come swimming with us!’ Rej Marsh calls. ‘We promise there won’t be math!’

The others laugh. They don’t mean it cruelly. I can smell the playfulness. Their invitation is genuine. It always is, and that makes me happy.

But I never go.

The other kids in the Brook ent mean, but they don’t understand me, either. Ent the math or the spelling that drove me out, or any of them. It’s all of them. The noise, the smells, the constant chatter. It was being inside with everyone in close, squeezing the air around me.

It’s better this way – safe in the trees, away from the splashing and shrieking, but present with my music. Sometimes they call out requests and sometimes I oblige, but mostly they act like I’m not there, and that’s fine with me.

The sun is setting as I circle back to Grandda’s farm for supper. I love dusk as much as I hate the dawn. Even indirect sunlight feels like a great fist, squeezing me throughout the day. But now that pressure is receding and it’s like waking up, feeling my senses expand and my powers return.

I’m almost home when I see fresh scars in the bark of a tall tree, throbbing with escaping heat.

My eyes flick around, noting similar marks on other trees as I follow the path to where the creature dropped down to the ground, leaving two great taloned footprints in the dirt.

Wood demon.

For the most part, corelings come in two types – Regulars and Wanderers. Regulars tend to hunt the same area every night. Wanderers roam about, following spoor trails and sound in search of prey. They can range for miles, coming in and out of a region.

Tibbet’s Brook was too far away to get purged of demons like the Free Cities did when Da destroyed the demon hive. But there were less out here to begin with, and Aunt Selia’s militia cleared out all the Regulars years ago.

Still, every once in a while a Wanderer finds its way onto someone’s property. If it finds prey, there’s a chance it might become a Regular. It’s hard to imagine one wandering so close to the farm’s greatward without drawing attention, but these prints are barely a day old.

Demons hate sunlight even more than I do. My skin burns easily, but they burst into flame. Like me, I expect they feel morning’s weight pressing on them long before the dawn. To escape they use their magic to dissipate, becoming insubstantial as they flee back underground using one of the natural vents magic uses to flow up from the Core.

But even Wanderers are creatures of habit. Whatever vent a coreling uses to escape the sun will be the same one it rises from the next night, which means the demon is still in the area.

I take a deep breath, and blow it slowly out my nostrils. Today had been such a quiet day. I have to tell everyone about this, but I already know what they’ll say.

When your da saves the world, folk have expectations.

* * * * *

I busy myself in the barn, but it’s really just an excuse to get out of the house. I’d rather listen in on the adults from here than sit there and have them talk like I’m invisible.

Aunt Selia and her wife Lesa came out to the farm when she got news of the Wanderer. Figured she’d call me out for stealing her butter cookies while she was here, but she din’t.

‘Boy’s got to learn to do things for himself, Ren,’ Grandda says.

Mam snorts. ‘How many summers did you have again, Jeph Bales, the first time you stood up to a demon on your property?’

‘Too many, and you know it.’ Grandda strikes a match, puffing at his pipe. ‘Like to think I raised my kids to be better than me.’

Mam doesn’t have a reply to that. ‘What do you think, Hary? Darin ready for this?’

‘Boy knows all the songs, backward and forward,’ Master Roller says. ‘Just… needs a bit of confidence.’

Ay, that’s a sunny way of putting it.

It ent that I’m scared of corelings, exactly. Been wandering around alone at night since I was old enough to walk. Come across demons plenty of times.

But I’m smart enough to avoid them. They want me to use my pipes to call one right to me.

‘Only way to get confident at a thing is to do it,’ Selia says. ‘Ent going to be by himself. Hary and me will be right there with him.’

‘New moon tomorrow,’ Mam notes.

Selia scoffs. ‘Ent seen more than the occasional Wanderer around these parts in ten years. Let the boy show what he can do.’ ‘Ay, all right,’ Mam says at last. ‘Reckon it’s time Darin started learning the family business.’